Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

A book for all artists; a book for all humanists. Not sure why it took so long for me to get around to reading this masterpiece, but the timing couldn’t be better as I finish my second novel with many of the same themes surrounding why we create art, why we live.

View all my reviews

novel, toil & sound, creative writing, short fiction, writing life

One-year anniversary giveaway for The Emergent

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Emergent

by Nick Holmberg

Giveaway ends March 31, 2023.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

The Emergent – a synopsis

“Unknowns can be handled in two ways. You can stay on the beach and watch, imagining what

might—but probably won’t—happen. Or you can offer up your mere physical existence for the

chance to be a part of something bigger than yourself.”

These are among the last words that Kat hears from her lifelong friend, Alma. The Emergent opens at the dawn of the internet era, and nineteen-year-old Silicon Valley native Kat is alone.

Haunted, she wonders if her actions drove Alma-and the rest of her family-away. Soon after

Alma’s disappearance, Kat finds herself in New York City with a new companion. In an apparent attempt to understand why she ended up across the continent, Kat relates her family’s story. Set in places like the shores of Oakland after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Depression-era farming communities of California’s Central Valley, and cold-war Santa Clara Valley, the family history and its ghosts also seem to shroud who Kat really is. But a series of mysterious injuries compel Kat to reveal more about herself. Will these revelations save Kat from her past? Or will they forever define her future?

Contact the author for a full tip sheet and to discuss speaking engagements.

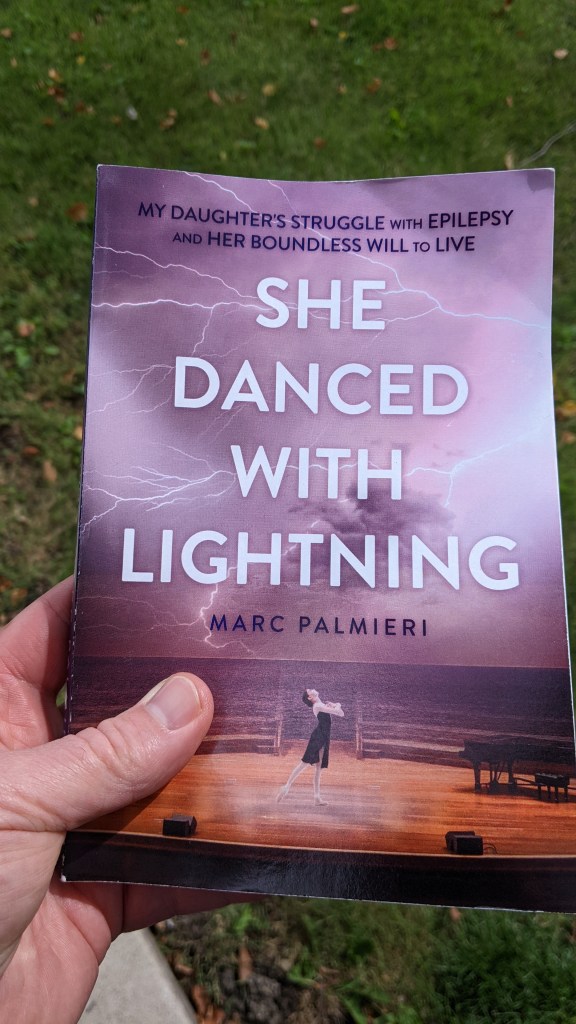

a dramatist’s memoir about epilepsy

A grad school pal from my ’03-’04 CCNY days is having a fantastic time doing a bit of a book tour. As an actor and college instructor, he is perfectly suited to engage and teach the public about his experiences caring for someone with a severe illness. And he’s a hell of a writer, too. She Danced with Lightning is a memoir of Marc Palmieri and his family navigating their daughter Anna’s epilepsy over the course of about a decade and a half.

Since the book’s recent publication, I’ve seen many people posting on social media how they could not put Marc’s book down. They must be of stronger stuff then me. Marc, a playwright of several produced dramas, writes with the dramatic tension that one would expect of, well, a dramatist. The ebbs and flows of terror that Marc depicts in his narrative were so evocative that I had to pace myself: death of a child and ruined marriage a definite possibility at every turned page. I could only read one chapter per sitting, experiencing Marc’s anxiety and helplessness in the face of the medical mystery that was Anna’s disability. This isn’t to say there aren’t moments of levity in this story (e.g. Marc’s concerns about being illegally in possession of medical marijuana; adolescent Anna’s mild Tourette-like symptoms brought on by the lesion buried in her brain). And there are moments in the story that are truly relatable: the life of the artist needing to juggle jobs while finding time to work on the next piece of writing.

Marc helps the reader understand that all things worth caring about take a hell of a lot of hard work, endurance, and faith. And for Marc to keep pressing forward in the face of such uncertainty would have been a far more daunting trial without a multitude of friends and family supporting him.

The Big Holiday Read

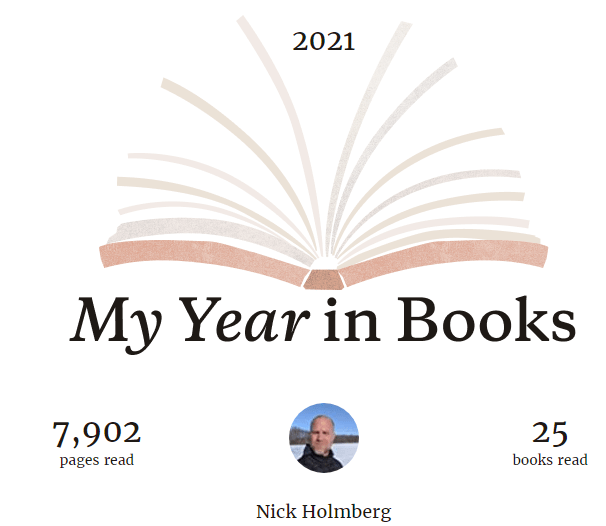

I’ve experienced 25 books this year. Granted, one of them was a children’s book. And much of my consumption consisted of audiobooks (can’t let my commute to work get in the way of a good story!).

But with a couple weeks off and my manuscript with the designer, I thought I’d try to reach 30 books by the end of the year by reading the hardcopies of the following books:

Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck by William Souder (120 pages in as of now; if you know me at all, you know JS is my jam)

The Last One by Fatima Daas (debut novel from a French queer Muslim woman)

The Samurai’s Garden by Gail Tsukiyama (recommended by Aunt Dayle)

One Man’s Initiation: 1917 by John Dos Pasos (how is it I’ve never read any Dos Pasos? This is his debut; I’ve asked Santa to bring me the USA Trilogy)

This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald (rounding out the debut novel semi-theme, not quite sure how I missed reading this one over the years)

What would you recommend for my 2022 booklist?

Queen Lizzy is Unimpressed

Nic and I linger over breakfast during the autumn, entertained by the squirrels playing, forgetting where their food is, getting fat. We root for them to make it across the street, cheer when they’ve lived to cross another street. It’s the same every year here in the Midwest. This year, however, those little rascals seem to be particularly abundant. And this means that squirrel demise is on the rise: hawks, cars, falls from trees, loose power lines dangling from our utility pole listed as the cause of death in the coroner’s report. More than usual, the dead rodent this year dots my consciousness like spilled ink. Or a spreading pool of blood, as it were.

I once knew someone who, for religious reasons, travelled with a shovel in the trunk of their car, giving roadkill dignified ceremonies for undignified deaths. I was never sure how this person got their PhD—or ever made it to work on time: stopping for every dead animal they drove past. I am fairly certain this person did not grow up in the Midwest, where the accidental slaughter of wild animals is part of the landscape.

I do understand the sentiment, though. So on the several occasions in the past year when a fallen (but completely intact) squirrel lay lifeless in the street in front of my house (victim of a slippery utility pole or its stray electrical current), I have scooped up the rust-and-beige body with my yellow snow shovel and transported it to the wooded areas behind the property. I don’t go so far as to bury the poor bastards; but in my mind, it is more dignified to return the little guys to nature; at least then all the fat that they worked so hard to pack on in the closing days of autumn will not have been for nothing. I mean, isn’t there more dignity in being a snack for a turkey vulture than to be a pavement Jackson Pollock, innards forced out of either end?

The latter seems like a waste (unless you’re a diehard art fan), while the former seems to serve a purpose.

Just the other day, I transported the second little body of the week to the long grasses just beyond the 3-foot fence at the back of the yard, an offering to scavengers or worms. And today I worked from home. My office commands a fantastic view of the park, the capitol building seeming to sit atop the tree line. Backyard tree now with bare limbs, I had a clear view of a well-fed red tail hawk. We’ll call her Queen Lizzy.

In the past couple years of mostly working from home, I have never seen Queen Lizzy in our tree; she lives in the park trees a good 100 yards distant from my office window. She is graceful, soaring high on warm drafts in summer and darting at lower altitudes in winter. So to see Queen Lizzy not 20 yards from me—her white breast contrasted with her brown feathers and the gray day—brought my work to a grinding halt.

Perched 15 feet up in the tree, she rotated her head 180 degrees each way. Then she spread her wings, quickly alighting on the 3-foot fence below. For several minutes, her head was on a swivel. She could not believe her good fortune, or she didn’t want anyone to see what she was about to do, or was looking at me incredulous at the stupidity of whatever animal she was hunting.

In a flash of brown-red-white, she hopped into the grass below, flew a few more feet and landed. It didn’t seem likely that the squirrel corpse I had laid there the day before would still be around: fox and coyote sometimes saunter through the park and they surely would have caught the scent of an easy meal. So I assumed Queen Lizzy had made a fresh catch of some living thing and was waiting for it to gasp its last under her death talons.

My curiosity got the best of me, as all I could determine from my vantage was that she was just standing over the body of her kill. I figured if she was startled by me, she could take her meal elsewhere in those death talons. I was a mere 15 yards from her when I stopped at the back fence line. She did not fly off immediately. Her dignity had suffered a blow: she was embarrassed for having thought the squirrel was alive, mortified to have been seen with a squirrel she herself had not caught. More than anything, though, she was unimpressed with my offering.

Queen Lizzy flew off, mumbling something about how dining al fresco didn’t mean the meal had to be cold, too.

a white dude’s reading list for white folks

This is my non-exhaustive reading recommendation list for white folks. In no particular order:

- Men We Reaped (2013) by Jesmyn Ward

- Native Son (1952) by Richard Wright

- Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen

- Invisible Man (1940) by Ralph Ellison

- Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) by Zora Neale Hurston

- White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (2018)* by Robin DiAngelo

- An American Marriage (2018) by Tayari Jones

- The Water Dancer (2019) by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- We Need New Names (2013) by NoViolet Bulawayo

- The Nickel Boys (2019) by Colson Whitehead

- The Residue Years (2013) by Mitchell S. Jackson

- Becoming (2018) by Michelle Obama

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) by Frederick Douglass

- Erasure (2001)* by Percival Everett

- The Sellout (2015) by Paul Beatty

- How To Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America (2013) by Kiese Laymon

*-not yet read; it’s near the top of my to-read list

A humble list of resources and black American perspectives

[You can read Part 1 of 2 here]

Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible…until you let the sun in.

No matter a person’s political affiliation (is there any such thing as an apolitical adult anymore?), they are likely to have one of four frames of mind about rioting:

- they understand it and condone it as a last resort of communicating outrage;

- they understand it but don’t condone it;

- they try to but don’t understand it and don’t condone it;

- they willfully remain ignorant and don’t take the time to try and understand it

The common denominator with all of these mindsets is that they belong to people who believe that rioting is not an ideal method of communication.

photo credit: Ryan Michalesko/The Dallas Morning News via AP

Today (and in the coming weeks, months, and lifetimes), white Americans have yet another opportunity to choose a riotous or non-riotous future:

- The status quo (which continues the unending cycle: invisible racism turning into visible racism, which leads to peaceful protests that often turn violent, followed by blaming and distracting from everything but the root cause; the last phase of the cycle is apathy)

- Change:

- Most importantly, learn what it means to be an ally. As my friend Melissa Roshan says, LISTEN! Assume only one thing: that you don’t know a goddamned thing about the daily injustices of systemic racism. Take action based on cues from people of color.

- Support and volunteer for political candidates who increase diverse representation in government, as my friend Dan Knewitz has been doing in Minneapolis for several years.

- Donate to organizations like Ethel’s Club so that the voices will be given to “artists, creators, and practitioners working to empower people of color… doing positive work in their communities.”

- Donate to after-school programs or schools with missions like Comp Sci High in the Bronx, where my old friend John Campos and the team of educators have made advancements in career opportunities through educational accessibility for under-served populations.

- No White Saviors

- The Conscious Kid

- Brittany Packnett

- Austin Channing Brown

- The Loveland Foundation

A brief history of 400 years of oppression

Last week (was it last week? it feels like a lifetime ago), I learned about the first Memorial Day. On May 1, 1865, thousands of freed enslaved people held a parade in honor of the hundreds of Union soldiers they had spent several days exhuming and properly re-burying; the bodies had been hastily buried in a mass grave by retreating Confederate troops only months before.

I was irritated that I had never before heard of the first Memorial Day. Then I saw the George Floyd video.

Then the protests and riots began.

“Los Angeles Protesters were among those who turned out in cities across the U.S. on Saturday to protest the death of George Floyd at the hands of police.”

(photo credit: Nam Y. Huh/AP)

The first Memorial Day came back into mind today as I continued trying to process the ongoing peaceful protests and riots across the country. Something occurred to me: the freed men and women who organized the original Memorial Day (Decoration Day) likely had at least two expectations. One, that their gesture would be understood as genuine gratitude for the Union that had, finally, ended slavery. And two, that their gesture would be unmistakably political. The parade, after all, was staged in the very city where the Civil War began: Charleston, South Carolina. Black Americans, in my humble estimation, were signaling that they expected to be recognized and respected for their own outsized contribution to America.

Wouldn’t it also be reasonable for the freed people to expect after May 1865 that race relations in America would be different for their descendants? Some 10% of the Union Army was comprised of black men (there probably would have been more if white lawmakers hadn’t been so afraid of arming too many), and 40,000 black soldiers would die by the time the war was finished. And slavery was over—at least legally and overtly.

After all that bloodshed, as well as 246 years of forced unpaid labor in America and 89 years of building the white ruling class’ monuments to themselves and their hollow documents of life and liberty, the freed men and women must have thought reparations were in order. At minimum, those reparations should have come in the form of good-faith efforts by white Americans to act on a founding tenet: all men are created equal.

And yet here we are again. Protests against racial injustice in America speak a truth that is self-evident.

Protests against police brutality and racial oppression is an American tradition. Watts (1965). Newark and Detroit (1967). 125 US cities (1968). Miami (1980). Los Angeles (1992). Cincinnati (2001). Ferguson (2014). Baltimore (2015). Charlotte (2016). And that is only over the last 55 years. It stands to reason that all the lynching which went unchecked by law & order from the 1870s to the late 1930s was a form of police brutality. Silence was consent. And that resulted in The Great Migration, during which black Americans were refugees in their own country.

Unfortunately, this migration didn’t change the system enough over the years, as there are no major cities in the US—north or south—that have been immune to the unrest over the decades. And even today, smaller Midwest towns and cities (e.g. DeKalb, Des Moines, Davenport, Madison) have seen peaceful protests turn to violence.

It is clear that there is a correlation between oppression and protests-turned-riots here in America. What is not clear, however, is how the protests turned violent. At least not yet with this most recent flare up. I am immediately suspicious of anyone who says with confidence that, “It is a subset of cops” or “It is white supremacists” or “It is Antifa” or “It is the anarchists.” In reality, any and all of these groups could have active provocateurs at the protests. The conditions of racial tension are ideal for any and all of these groups to achieve their aim: to sow discord (albeit for different ends). It is also true that the group(s) responsible for inciting the violence really just depends on which “news” service or social media “friend” can provide an individual’s preferred narrative.

In the end, who instigated the riot in Minneapolis or Anywhere, USA doesn’t fucking matter. The conditions for peaceful protests and riots as they pertain to race are ever-present but often invisible, especially to the white majority. It’s just that now—as at so many other times in America’s turbulent, oppressive past—the conditions exist in which the murder of another unarmed black person is held up and examined in the light from the flames of another burning police car.

Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible…until you let the sun in.

[Tune in tomorrow for part 2 of 2: [a humble list of resources and American black perspectives]

the semi-urban fox

I’ve never been good at humor; I’m really good at anxiety and staring at walls in brief bouts of depressive catatonia. Getting really good at those things these days.

I’m not good at producing humor. I try, but I’m no good at it. I know it when I hear it and usually when I read it. But I can’t tell jokes very well, and I can’t write funny stuff (just look at my FB posts recently), and I am only beginning to experiment with dark satire (see Stratovirus-19 installments elsewhere on this blog). It’s all that much harder these days to just be plain funny without it all wrapped up in blue-state this and red-state that…Conan O’Brien does it by being humble, self-effacing, and recently/usually steering clear of politics (there’s no shortage of comedians doing politics these days, and that’s important in its own right). This is the time we need humor, as serious and goddamned deadly as these times are.

See? There I go again.

But if I die before I learn to tell a joke and comedy can’t bring people together, maybe there’s another way. What follows is not poetry (I used to be okay at that, but not anymore), but it’s me.

Carbon is not a man, nor salt nor water nor calcium. He is all these, but he is much more, much more; and the land is so much more than its analysis.

–John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath (p. 158)

Got up today long before my snoozing and snoring co-quarantining beings. I crept down to the backyard and communed with the chilly air, the sunrise, and the chirping of thousands of birds. I tried to hear my beloved cardinals and their distinct calls, but I gave up and leaned back, the light growing a paler orange.

I didn’t want to but I knew I had to go on a run. I rousted the pooch and headed down to the trail along the banks of the Des Moines River heading southeast. A couple people lurked in the brush, cast us looks suspicious or otherwise, and we ran on. About a mile in, two doe crossed the path from their drinking spot in the river about 50 yards ahead and bounded into the brush. I spotted them casually watching us as we passed.

Another doe leaped across the path into the brush a bit later and Frank alerted to it. I think back to a couple lifetimes ago (Fall 2016) when four doe passed by the softball field where we were playing early morning fetch in DeKalb, IL. Frank alerted and ran toward them; fortunately, he saw the size difference and didn’t feel the need to pursue them through the opening in the fence. He would have been trampled, if not humiliated by his inability to get the deer to play fetch with him. He could probably catch a squirrel, but he wouldn’t know what to do if he did. Besides, he’d have to drop his tennis ball to really catch the critters, those taunting ubiquitous tree rodents.

We turned around and ran back the way we came, and I scanned the underbrush near the river, looking for the beaver Nic said she saw the other day; or I was looking for the white feral cat that I once saw skulking on a hunt as I ran by; when I passed by ten minutes later, the savvy bastard had a field mouse freshly killed in its mouth. But on this morning’s run, no such drama. No usual redtail hawks gliding overhead. No owls calling to each other from their roosts after a long night of hunting, as if to say, “It was a good night. Whoooo shall we kill tonight? Sleep well, neighbor.”

I wonder how the naïve young rabbits—those cute little guys Nic and I call Jenkins, Jimmy Carrots, and Baby Carrots as if they were the same ones we named all those years ago in DeKalb—I wonder how they or their mothers ever sleep, what with the deadly graceful daytime hawk drafting before diving and the big-eyed nighttime assassin swooping.

“[Dr. David] Drake hopes the urban canid project can encourage city dwellers to engage with the natural environments around them and inform decision-making among wildlife managers. With a rapidly urbanizing global society and increasing pressure on wild places, it behooves humans to better understand the animals that share their spaces…”

–Will Cushman (2019), “Lives of the Urban Coyotes and Foxes“

And I wonder if I’ll ever see a wild fox again like the one I saw in DeKalb while oblivious Frank chased his tennis ball across the infield. Red coat ablaze in the early autumn sunrise, trotting confidently from behind the car across the parking lot and into a stand of trees, a fox is the semi-urban Midwest morning.

Photo courtesy of the UW-Madison Urban Canid Project.